The show in question has always been a delight. Much loved and often revived in in the 1930s and 40s Emlyn Williams’s autobiographical play tells the story of how a determined middle-aged woman arrives from England to take up residence in a small Welsh Village. She sets up a school and takes one of the most promising pupils (our author) under her wing, attempting to groom him for Oxford.

There’s absolutely nothing demanding or gritty about this piece which rattles along pleasingly and predictably in the way you might imagine. Set as it is in a mining community at the turn of the last century all the local village archetypes are present and correct. As you would expect there’s a crusty local landowner to be won over, a pontificating local preacher and twittering local spinster to be recruited to teach at the school and the lads from the pit arrive boisterously, but not too boisterously, are soon won over, and are supplemented on this occasion by an additional male-voice-choir given to emerging from the gloom carrying lanterns, smeared with coal dust and singing gorgeous harmonies as underscoring to the central action. It’s the type of whimsical, nostalgic piece that has no time to dwell on the horrors of the miner’s life, indeed the only suggestion that this may not be a walk in the park is a brief reference to a boy whose lung has been damaged.

The teacher at the central of all this is Miss Moffat, modelled on a teacher from the playwright’s own life who had a profound effect on him, encouraging him to study and later to go into the theatre. It’s a role that’s been cherished by many great actresses including Katherine Hepburn, Deborah Kerr and even Bette Davies, and on this occasion, it is performed by the adorable Nicola Walker. A whirlwind of brisk forthrightness, plain speaking, and flashes of kindness she’s the kind of bossy older sister we all wish we had. The plot places very few obstacles in her path to success and those she does encounter are batted away with unfaltering quick wittedness with barely a moment of self-doubt or introspection. It is only in the last twenty minutes of the play that a credible threat to her student’s future emerges

The hand of Director Dominic Cooke is very much in evidence throughout. In his staging the curtain rises, not on a naturalistic setting but on the silhouette of the playwright marooned and amidst a gaggle of English high society dancing the Charleston. Returning to his room he types and recites the opening stage directions. The characters emerge from the darkness on to a bare platform and act out what he is describing. They begin without props but then slowly, as the piece goes on, with the figure of the playwright always present, the staging, designed by Ultz, becomes fuller until after the interval we are at last presented with the fully realised school room.

I must confess I didn’t particularly enjoy this bolted on directorial conceit because I know, having long ago appeared in the play as the Oxford bound Morgan Evans, that it can charm amuse and move audiences very well on its own without the director constantly reminding us that it’s autobiographical. However, it would be wrong of me not to recognise everyone around me seemed to love the contemporary theatricality of all this and the general opinion is that Cooke has given a creaky old play new life by inviting us to consider the greater implications of the action as a social commentary on the period and insight into the writer’s psyche.

For me such scrutiny suddenly exposed the plays weaknesses. For example, if we are invited to initially keep Miss Moffat at arm’s length and consider her as a proto-type feminist, she’s a very odd one. Completely invested in the male characters and rather dismissive of the females she never notices or questions that her school is populated entirely by boys. What the girls are up to, and why she doesn’t care, remains a mystery.

But these are minor quibbles. The audience positively purred with pleasure throughout the two and half hours playing time which flew by. You’ll have a great time too and there’s every sign that the National Theatre finally has a hit on its hands.

There hasn't been much good news for the National Theatre in recent years. What was left of a schedule ravaged by COVID has all too often been savaged by the critics. So it was a delight to be amidst an audience emerging from a show there, for once, buzzing, happy and contented, having had a great evening.

There hasn't been much good news for the National Theatre in recent years. What was left of a schedule ravaged by COVID has all too often been savaged by the critics. So it was a delight to be amidst an audience emerging from a show there, for once, buzzing, happy and contented, having had a great evening.

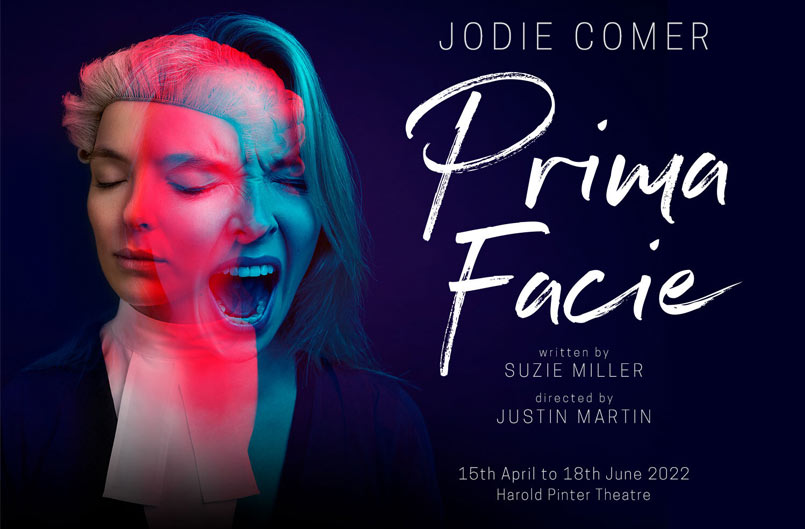

In Suzie Miller’s play

In Suzie Miller’s play